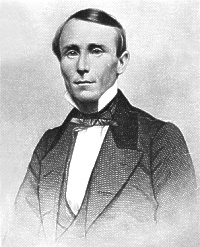

President of Lower California, Emperor of Nicaragua, doctor, lawyer, writer—these were some of the titles claimed by William Walker, the greatest American filibuster.

President of Lower California, Emperor of Nicaragua, doctor, lawyer, writer—these were some of the titles claimed by William Walker, the greatest American filibuster.

In the mid-nineteenth century, adventurers known as filibusters participated in military actions aimed at obtaining control of Latin American nations with the intent of annexing them to the United States—an expression of Manifest Destiny, the idea that the United States was destined to control the continent. Only 5’2″ and weighing 120 pounds, Walker was a forceful and convincing speaker and a fearless fighter who commanded the respect of his men in battle.

Born in 1824 in Tennessee, Walker graduated from the University of Nashville at the age of 14 and by 19 had earned a medical degree. He practiced medicine in Philadelphia, studied law in New Orleans, and then became co-owner of a newspaper, the Crescent, where the young poet Walt Whitman worked. When the paper was sold, Walker moved on to California, where he worked as a reporter in San Francisco before setting up a law office in Marysville.

When he was 29, his freebooting nature led him to become the leader of a group plotting to detach parts of northern Mexico. Recruiting a small army, he sailed to Baja California and conquered La Paz, declaring himself president of Lower California. He then decided to extend his little empire to include Sonora, and renamed it “The Republic of Sonora.”

Marching on to the Colorado River, Walker found himself faced with harsh conditions and a high desertion rate, forcing him to retreat to California, where he surrendered to U.S. authorities on charges of violating U.S. neutrality laws.

One result of this incursion was that Mexico sold a part of Sonora to the United States—the transaction we call the Gadsden Purchase. Acquitted of criminal charges, Walker next turned his attention to Central America. Throughout this region, chaos reigned, as forces known as Democrats and Legitimists fought each other. The leader of the Democratic faction in Nicaragua invited Walker to bring an army and join the struggle against the Legitimists. In 1855, with his army of 58 Americans, later called by stateside romantics, “The Immortals,” he landed in Nicaragua.

Within a year, leading “The Immortals” and a native rebel force, he routed the Legitimists and captured Granada, their capital. His success roused concern in the other Central American countries, especially Costa Rica, which sent in a well-armed force to invade Nicaragua. Walker’s army repelled the invasion, but a poorly executed counter attack into Costa Rica failed, and a war of attrition continued, in which disease killed more soldiers on both sides than enemy bullets.

Other enemies plagued Walker. Cornelius Vanderbilt, the shipping magnate, seeking control of the San Juan River-Lake Nicaragua route from the Caribbean to the Pacific, armed Walker’s enemies, while the British navy, attempting to thwart American influences in the region, regularly harassed efforts to supply him. In spite of these factors, Walker had himself elected president of Nicaragua. The United States briefly recognized his government but never sent him aid. Soon the other countries of Central America formed an alliance against him, and in mid 1857 he surrendered once again to a U.S. naval officer and returned to the U.S.

Landing first in New Orleans, he was greeted as a hero. He visited President Buchanan, then went on to New York, all the time seeking support for a return to Nicaragua. But support waned as returning soldiers reported military blunders and poor management.

Nevertheless he succeeded in raising another army, and returned to Nicaragua in late 1857. Again thwarted by the British navy, he abandoned his third Latin American invasion.

Still undaunted and seeking support for yet another venture, Walker wrote a book, The War in Nicaragua. Knowing that his best prospects lay in the South, he assumed a strong pro-slavery stance. This strategy proved successful, and in 1860 he once again sailed south. Unable to land in Nicaragua due to the ever-present British, he landed in Honduras, planning to march overland, but the British soon captured him and turned him over to the Hondurans. Six days later, at the age of 36, he was executed by a firing squad. The Walker saga had ended. This enigmatic man had come close to altering the history of the continent. Had he been successful, he might have brought several Central American countries into the United States as pro-southern states, altering the balance in Congress and postponing The Civil War.

Today Walker is far better known in Central America than in the United States. Costa Ricans honor Juan Santamaria, a young drummer boy who became a national hero by torching a fort in which Walker’s army was encamped, and a national park, Santa Rosa, commemorates the battle where Walker’s soldiers were expelled from Costa Rica.

“Get out there and loot!” she seemed to squawk as she roughly shoved her mate out of the nest. He looked about, spotted a nest whose residents had temporarily left unattended, snatched some nesting material from it, and hurried back to his sweetie who nuzzled him appreciatively before sending him out again on another pillaging mission.

“Get out there and loot!” she seemed to squawk as she roughly shoved her mate out of the nest. He looked about, spotted a nest whose residents had temporarily left unattended, snatched some nesting material from it, and hurried back to his sweetie who nuzzled him appreciatively before sending him out again on another pillaging mission. President of Lower California, Emperor of Nicaragua, doctor, lawyer, writer—these were some of the titles claimed by William Walker, the greatest American filibuster.

President of Lower California, Emperor of Nicaragua, doctor, lawyer, writer—these were some of the titles claimed by William Walker, the greatest American filibuster.