Easter in Copper Canyon is the most colorful time of year. Small towns which are sleepy most of the year now are full of tourists—both Mexican and foreign—who have come to see the Easter celebrations of the Tarahumara Indians. The tourists cluster with their cameras in the Indian villages, but most of them have little idea of what is going on.

To begin to understand the Tarahumara ceremonies, one has to have a basic understanding of the Indians’ religion. The Tarahumara are outwardly Catholic, but their version of Catholicism is unlike any form we are familiar with.

To begin to understand the Tarahumara ceremonies, one has to have a basic understanding of the Indians’ religion. The Tarahumara are outwardly Catholic, but their version of Catholicism is unlike any form we are familiar with.

In 1602, the Jesuits brought Christianity to the Indians, who adopted it, but interpreted and modified it to conform to their own customs and ideas. In 1767, King Charles III of Spain expelled the Jesuits from the New World, and the Tarahumara, on their own now, continued to develop their religious beliefs and rituals. Their resulting theology is as follows:

God is the father of the Tarahumara and is associated with the sun. His wife, the Virgin Mary, is their mother and is associated with the moon. God has an elder brother, the Devil, who is the uncle of the Indians. The Devil is the father of all non-Indians, whom the Tarahumara call chabóchi, “whiskered ones.” At death, the souls of the Tarahumara ascend to heaven while those of the chabóchi go to the bottommost level of the universe.

The well-being of the Tarahumara depends on their ability to maintain the proper relationship with God and the Devil. God is benevolent, but they must not fail to reward His attentions adequately. The Devil is the opposite, and will cause the Indians illness and misfortune unless they propitiate him with food. God is pleased by the dancing, chanting, feasting, and offerings of food and corn beer, that are a part of all Tarahumara religious festivals. The Devil is also pleased because the Indians bury food for him at these fiestas.

Of all the religious ceremonies throughout the year, The Easter celebrations are the most important. Hundreds of men, women, and children converge on the local church from villages as far away as fifteen miles. These celebrations are for socializing and having a good time, but the Indians also expect their efforts to please God so that He will give them long lives, abundant crops, and healthy children.

The Easter rituals concern the relationship between God and the Devil. Although God and the Devil are brothers, and occasionally get along, the Devil is usually bent on destroying God. Most of the time God fends the Devil off.

But each year, immediately prior to Holy Week, the Devil succeeds by trick or force in rendering God dangerously vulnerable. The Easter ceremonies are intended to protect and strengthen God so that He can prevent the Devil from destroying the world.

Each of the men and boys of the community takes part in the ceremonies as a member of one of two groups. The first group, the Pharisees, are the Devil’s allies, and carry wooden swords, painted white with ochre designs. The second group, the Soldados, the Soldiers, are allied with God, and carry bows and arrows.

The celebrations begin on the Saturday prior to Palm Sunday, with speeches and ritualized dances. The Pharisees, their bodies smeared with white earth, and the Soldados dance to the beating of drums and the melody of reed whistles. About midnight, a mass is held in the church. Shortly after sunrise, bowls of beef stew, stacks of tortillas and tamales and bundles of ground, parched maize, are lifted to the cardinal directions, allowing the aroma to waft heavenward to be consumed by God. The food is then distributed among the people. At mid-morning the Soldados and Pharisees set up wooden crosses marking the stations of the cross, a mass is held, and the priest leads a procession around the churchyard, with the participants carrying palm branches.

Three days later, on Holy Wednesday, the ceremonies resume, and for the next three days there are processions around the church. The point of the processions is to protect the church and, by extension, God and God’s wife.

On the afternoon of Good Friday, the Pharisees appear with three figures made of wood and long grasses representing Judas, Judas’s wife, and their dog. To the Indians, Judas is one of the Devil’s relatives, and they call him Grandfather and his wife Grandmother. Judas and his wife wear Mexican-style clothing and display their oversized genitalia prominently. The Pharisees and Soldados parade the figures around the church, dancing before them. The Pharisees then hide the figures away for the night.

On Saturday morning, the Soldados and Pharisees engage in wrestling matches, battling symbolically for control of Judas. The Soldados then take possession, shoot arrows into the three figures and set them afire. The people retire to continue the celebrations at the many tesguino drinking parties.

In Mexico’s Copper Canyon

In Mexico’s Copper Canyon

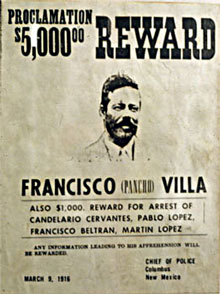

Pancho Villa, so the saying goes, was “hated by thousands and loved by millions.” He was a Robin Hood to many and a cruel, cold-blooded killer to others. But who was this colorful controversial hero of the Mexican Revolution and where did he come from?

Pancho Villa, so the saying goes, was “hated by thousands and loved by millions.” He was a Robin Hood to many and a cruel, cold-blooded killer to others. But who was this colorful controversial hero of the Mexican Revolution and where did he come from? Pancho Villa was a natural leader and was very successful as a bandit, leading raids on towns, killing, and looting. He was also involved in more legitimate ventures, including being a contractor on the Copper Canyon railroad.

Pancho Villa was a natural leader and was very successful as a bandit, leading raids on towns, killing, and looting. He was also involved in more legitimate ventures, including being a contractor on the Copper Canyon railroad. Most Americans think that Cinco de Mayo (the 5th of May) celebrates Mexican Independence Day. Not so. Mexican Independence Day is September 16. Then what is Cinco de Mayo?

Most Americans think that Cinco de Mayo (the 5th of May) celebrates Mexican Independence Day. Not so. Mexican Independence Day is September 16. Then what is Cinco de Mayo? Napoleon enlisted England and Spain to join him in a mission to encourage Mexico to pay off its foreign debts. The mission began with the landing of French, English and Spanish troops at Vera Cruz. The French minister then demanded that Mexico pay 12 million pesos to France, an impossible amount, given the state of the Mexican treasury.

Napoleon enlisted England and Spain to join him in a mission to encourage Mexico to pay off its foreign debts. The mission began with the landing of French, English and Spanish troops at Vera Cruz. The French minister then demanded that Mexico pay 12 million pesos to France, an impossible amount, given the state of the Mexican treasury. Thanks to you and

Thanks to you and  The tea we are offered at the airport, and again in our hotel lobby, is mate de coca—brewed from leaves of the coca plant. Coca is best known to North Americans as the source of the drug cocaine, which is actually a highly processed derivative of the coca leaf. Because of its association with the drug, coca is banned in the U.S.

The tea we are offered at the airport, and again in our hotel lobby, is mate de coca—brewed from leaves of the coca plant. Coca is best known to North Americans as the source of the drug cocaine, which is actually a highly processed derivative of the coca leaf. Because of its association with the drug, coca is banned in the U.S. This is Batopilas, a small village located in Mexico’s Sierra Madres at the bottom of the deepest canyon in the vast complex of mountains and canyons known collectively as

This is Batopilas, a small village located in Mexico’s Sierra Madres at the bottom of the deepest canyon in the vast complex of mountains and canyons known collectively as  Three miles downstream from Batopilas, past an old suspension bridge, is a 400 year old Jesuit mission. The mission, recently restored, is known as the “Lost Cathedral” of Satevo, because over the course of time all records of it were lost by the Catholic Church.

Three miles downstream from Batopilas, past an old suspension bridge, is a 400 year old Jesuit mission. The mission, recently restored, is known as the “Lost Cathedral” of Satevo, because over the course of time all records of it were lost by the Catholic Church. To begin to understand the Tarahumara ceremonies, one has to have a basic understanding of the Indians’ religion. The Tarahumara are outwardly Catholic, but their version of Catholicism is unlike any form we are familiar with.

To begin to understand the Tarahumara ceremonies, one has to have a basic understanding of the Indians’ religion. The Tarahumara are outwardly Catholic, but their version of Catholicism is unlike any form we are familiar with.