In the United States we honor the Irish on Saint Patrick’s Day, the Italians on Columbus Day, and the Mexicans on Cinco de Mayo. But what the heck is Cinco de Mayo?

Most Americans think that Cinco de Mayo (the 5th of May) celebrates Mexican Independence Day. Not so. Mexican Independence Day is September 16. Then what is Cinco de Mayo?

Most Americans think that Cinco de Mayo (the 5th of May) celebrates Mexican Independence Day. Not so. Mexican Independence Day is September 16. Then what is Cinco de Mayo?

After Mexico won its independence from Spain in 1821, it went through forty years of internal power struggles and rebellions. By 1861 the country’s finances were so bad that the nation owed 80 million pesos in foreign debts. Mexico’s president, Benito Juarez, pledged to pay off these debts eventually but, as an emergency measure, he suspended all payment for two years.

In France, Napoleon III saw this as an opportunity to establish French colonies in Latin America. He believed that the United States was too involved with the Civil War to try and enforce the Monroe Doctrine, and that if the South won the war—and after the Battle of Bull Run it looked like they might—opposition to his plan would be minimal.

Napoleon enlisted England and Spain to join him in a mission to encourage Mexico to pay off its foreign debts. The mission began with the landing of French, English and Spanish troops at Vera Cruz. The French minister then demanded that Mexico pay 12 million pesos to France, an impossible amount, given the state of the Mexican treasury.

Napoleon enlisted England and Spain to join him in a mission to encourage Mexico to pay off its foreign debts. The mission began with the landing of French, English and Spanish troops at Vera Cruz. The French minister then demanded that Mexico pay 12 million pesos to France, an impossible amount, given the state of the Mexican treasury.

Napoleon then set up a provisional government with his personal emissary as its head, and brought in a much larger French army to enforce it. England and Spain, now realizing Napoleon’s scheme for French domination, protested France’s moves and withdrew their forces.

The French, now alone, marched 6000 dragoons and foot soldiers to occupy Mexico City. On May 5 (Cinco de Mayo), 1862, on their way to the capital, the French soldiers entered the town of Puebla. To stop the French, the Mexicans garrisoned a rag-tag army of 4000 men at Puebla, most of them armed with fifty-year-old antiquated guns. The French general, contemptuous of the Mexicans, ordered his men to charge right into the center of the Mexican defenses.

The handsomely uniformed French cavalry charged through soggy ditches, over crumbling adobe walls, and up the steep slopes of the Cerro de Guadalupe, right into the Mexican guns. When the shooting was over, the French ended up with a thousand dead troops. The Mexicans then counter-attacked and drove the French all the way to the coast.

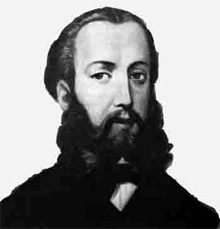

Now the honor of France was at stake. Napoleon III committed an additional 28,000 men to the struggle. They eventually took over Puebla and Mexico City. Napoleon next arranged for the young archduke Maximilian (photo above), brother of Austria’s Emperor Franz Joseph, to establish himself as emperor of Mexico, as a way to set up a legitimate-seeming government, while insuring French interests in Mexico. Maximilian’s reign lasted just three years. On June 19, 1867, he was executed by a firing squad, four months after the last French troops left the country.

Every 5th of May in Mexico, school children throughout the country celebrate the victory of the Mexican people over the French at the Battle of Puebla, but these celebrations are minor compared to their counterparts in the United States, where millions of Americans drink beer, eat tacos and hold parties to celebrate Cinco de Mayo, even though they have no idea what the holiday is all about.

Thanks to you and

Thanks to you and  This is Batopilas, a small village located in Mexico’s Sierra Madres at the bottom of the deepest canyon in the vast complex of mountains and canyons known collectively as

This is Batopilas, a small village located in Mexico’s Sierra Madres at the bottom of the deepest canyon in the vast complex of mountains and canyons known collectively as  Three miles downstream from Batopilas, past an old suspension bridge, is a 400 year old Jesuit mission. The mission, recently restored, is known as the “Lost Cathedral” of Satevo, because over the course of time all records of it were lost by the Catholic Church.

Three miles downstream from Batopilas, past an old suspension bridge, is a 400 year old Jesuit mission. The mission, recently restored, is known as the “Lost Cathedral” of Satevo, because over the course of time all records of it were lost by the Catholic Church. To begin to understand the Tarahumara ceremonies, one has to have a basic understanding of the Indians’ religion. The Tarahumara are outwardly Catholic, but their version of Catholicism is unlike any form we are familiar with.

To begin to understand the Tarahumara ceremonies, one has to have a basic understanding of the Indians’ religion. The Tarahumara are outwardly Catholic, but their version of Catholicism is unlike any form we are familiar with.

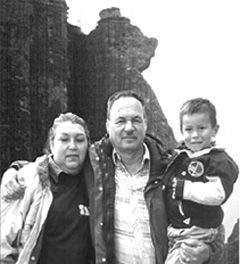

Born in a rural Ohio farming community, Doug has followed many diverse paths. He was an army sergeant, a NASA electrical technician, an editor, a deputy sheriff, a bodyguard, and now an inn keeper. His greatest passion is horses—he owns at least a dozen, and he brags that they are the best trained and equipped in Northern Mexico.

Born in a rural Ohio farming community, Doug has followed many diverse paths. He was an army sergeant, a NASA electrical technician, an editor, a deputy sheriff, a bodyguard, and now an inn keeper. His greatest passion is horses—he owns at least a dozen, and he brags that they are the best trained and equipped in Northern Mexico.