A dusty cowboy rides his horse down the sunbaked-earth main street, his pistol at his side. A small group of Indians, clad in bright colored blouses, breech cloths and headbands, pack their burros for the long journey back to their remote village, while nearby a group of children play tag around the bougainvilleas in the town square.

This is Batopilas, a small village located in Mexico’s Sierra Madres at the bottom of the deepest canyon in the vast complex of mountains and canyons known collectively as Copper Canyon. Today Batopilas is a sleepy little village, but it was not always this way. At the turn of the century it was one of the richest silver mining areas in the world, but after that period, time seems to have stood still.

This is Batopilas, a small village located in Mexico’s Sierra Madres at the bottom of the deepest canyon in the vast complex of mountains and canyons known collectively as Copper Canyon. Today Batopilas is a sleepy little village, but it was not always this way. At the turn of the century it was one of the richest silver mining areas in the world, but after that period, time seems to have stood still.

The Spaniards first mined ore in Batopilas in 1632, and the mines continued to produce for the next three hundred years. The peak mining period was reached during the late 1800’s when an American named Alexander Shepherd developed the mines to their highest level of production—a level which ranked them among the richest silver mines in the world.

The mining operation at that time employed 1500 workers, and the total length of tunnels was more than 70 miles. Shepherd did much to improve the town, building bridges, aqueducts, and a hydroelectric plant, which made Batopilas the second city in Mexico to have electricity—second only to Mexico City itself. His headquarters was known as the Hacienda de San Miguel—a complex of adobe buildings which included the family residence, the business offices and a mill and reduction plant. He later constructed the Porfirio Diaz tunnel—a tunnel bored through the base of a mountain, where a train hauled out ore which was dropped down shafts from the tunnels above. The train had to be dismantled and hauled in almost 200 miles by burro and human labor, because there was no road to Batopilas. In fact, the road to Batopilas was not built until the 1970’s, almost a century later. The tunnel is still there, now deserted except by the bats.

Today there is no large-scale mining in Batopilas, though a few old prospectors still pan gold and silver from the river or extract small quantities of ore from the abandoned workings.

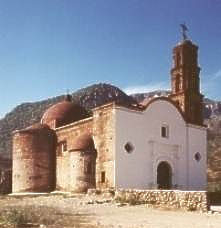

Three miles downstream from Batopilas, past an old suspension bridge, is a 400 year old Jesuit mission. The mission, recently restored, is known as the “Lost Cathedral” of Satevo, because over the course of time all records of it were lost by the Catholic Church.

Three miles downstream from Batopilas, past an old suspension bridge, is a 400 year old Jesuit mission. The mission, recently restored, is known as the “Lost Cathedral” of Satevo, because over the course of time all records of it were lost by the Catholic Church.

Most of the buildings in Batopilas were built during the Victorian Era, but some date back to the 17th century. Many of the businesses have no signs on them—after all, in a town the size of Batopilas everyone knows where everything is. In the general store the counters are the old-fashioned high ones, worn smooth and wavy from a century of customers resting their elbows on them.

Evening is a special time in Batopilas. As the twilight spreads over the little town square the residents gather to visit with their neighbors, share the events of the day, and relax. Meanwhile, the youngsters play basketball until it is time for bed.

Traveling to Batopilas is an adventure in itself. Beginning in Creel, the road travels up and down through mountains and valleys and finally, just outside of the Tarahumara Indian village of Kirare, heads straight down along a windy, twisted, one-lane, “E-ticket ride” dirt road to the bottom of the canyon. From there it hugs the side of the canyon as it follows the Rio Batopilas down river for another hour, finally arriving in Batopilas after 5½ to 8 hours, depending on whether you travel by car or take the local bus. The local bus is a rickety old school bus which makes the trip down from Creel every other day. For the return trip, the bus departs Batopilas at 4:30 a.m. so that it can reach the rim of the canyon before the radiator boils over.

The journey to Batopilas is a breathtaking trip, but is not suitable for all travelers as the road down may make the faint-of-heart wish they had stayed at home. The best time to make the journey down is in the winter time, because Summer temperatures can soar above 100° Fahrenheit

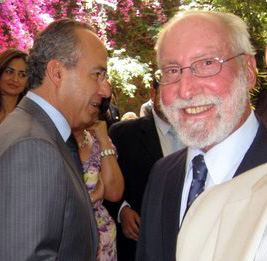

On May 21, 2010, California Native owners Lee and Ellen Klein were guests of Mexico’s President Felipe Calderón at a luncheon he held in Mexico City at Los Pinos, Mexico’s official presidential residence.

On May 21, 2010, California Native owners Lee and Ellen Klein were guests of Mexico’s President Felipe Calderón at a luncheon he held in Mexico City at Los Pinos, Mexico’s official presidential residence.

This is Batopilas, a small village located in Mexico’s Sierra Madres at the bottom of the deepest canyon in the vast complex of mountains and canyons known collectively as

This is Batopilas, a small village located in Mexico’s Sierra Madres at the bottom of the deepest canyon in the vast complex of mountains and canyons known collectively as  Three miles downstream from Batopilas, past an old suspension bridge, is a 400 year old Jesuit mission. The mission, recently restored, is known as the “Lost Cathedral” of Satevo, because over the course of time all records of it were lost by the Catholic Church.

Three miles downstream from Batopilas, past an old suspension bridge, is a 400 year old Jesuit mission. The mission, recently restored, is known as the “Lost Cathedral” of Satevo, because over the course of time all records of it were lost by the Catholic Church.