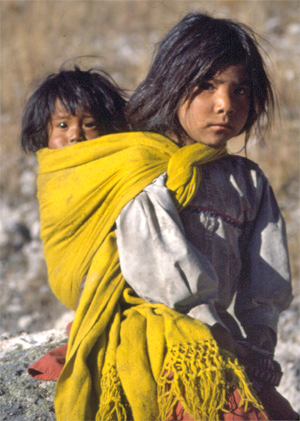

Deep in the heart of Mexico’s Sierra Madres, in the town of Creel, the center of Copper Canyon country, is the clinic of Santa Teresita. The lives of thousands of Tarahumara Indian children have been saved here because of the dreams and dedication of one man, Father Luis Verplancken.

Deep in the heart of Mexico’s Sierra Madres, in the town of Creel, the center of Copper Canyon country, is the clinic of Santa Teresita. The lives of thousands of Tarahumara Indian children have been saved here because of the dreams and dedication of one man, Father Luis Verplancken.

Father Verplancken was a Jesuit priest who first visited the Tarahumaras in the late 1950s. He saw a great need for health care for these Indians who inhabit this remote area of mountains and canyons. At the time their children had an alarmingly high mortality rate.

Verplancken put his ideas into action by starting a traveling health care facility, housed in a 4-wheel drive station wagon. He quickly discovered that a little help went a long way—one dollar’s worth of penicillin, for example, could treat hundreds of children.

The word spread and by 1964, Verplancken and his volunteers received enough donations to establish a small hospital in an old railroad warehouse. The demand for medical care was so great that some Tarahumaras walked three days from their remote villages to reach the hospital.

A major obstacle that both the town and the hospital faced was the lack of a dependable water supply. With the help of more donations, a pipeline was built from the nearest fresh water source, which was four miles away over extremely harsh terrain. Three handcrafted pumping stations had to be constructed to lift the water 600 feet up to the level of the town. For the first time, Creel and the hospital had a dependable supply of fresh water.

In the mid-1970s, plans were drawn for a more modern hospital. With the help of his nephew, who was studying architecture at the time, Verplancken designed what today is known as the clinic of Santa Teresita. This clinic was literally “hand-made.” Along with a dedicated group of volunteers, Father Verplancken quarried the stone, crafted the brick and cut the trees.

The clinic opened in 1979, and houses a seventy-bed hospital with x-ray and laboratory facilities, a pharmacy, dental facilities and an outpatient clinic.

After 52 years of service to the Tarahumara community, Father Verplanken died of cancer, but the clinic lives on.

Today, the clinic still depends on volunteers and donors. Over 90% of the services and medications are provided free of cost, and the remainder are provided to the local residents at a token fee.

Many guests on California Native Copper Canyon tours have visited the clinic and donated money, medicines and supplies. One woman, after returning from a recent trip, sent four sets of crutches that she purchased at a garage sale in the United States.

Now is the time to book your trip for Easter in Mexico’s

Now is the time to book your trip for Easter in Mexico’s

As we come to the end of another year, it’s time to reflect on what we have accomplished in the last year and what we are looking forward to in the new year.

As we come to the end of another year, it’s time to reflect on what we have accomplished in the last year and what we are looking forward to in the new year.

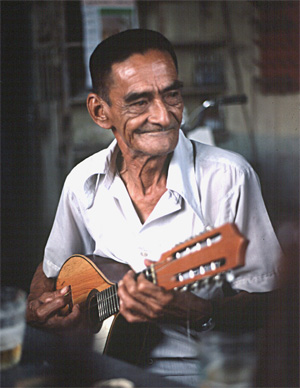

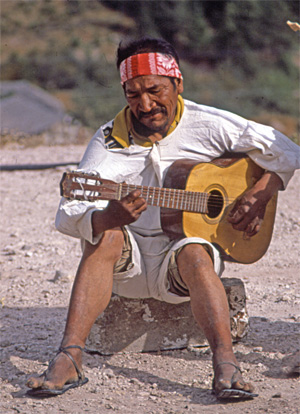

What in the world is a Tico? Sounds exotic. Maybe it’s something like a Piña Colada or a Cappuccino. Or maybe it’s one of those little biting pests that you find in tropical places. Wrong! A Tico is a very special group of people that inhabit one of the most beautiful, tropical and hidden paradises in the world—

What in the world is a Tico? Sounds exotic. Maybe it’s something like a Piña Colada or a Cappuccino. Or maybe it’s one of those little biting pests that you find in tropical places. Wrong! A Tico is a very special group of people that inhabit one of the most beautiful, tropical and hidden paradises in the world—