Down in the little town of Batopilas, tucked deep within the folds of Mexico’s Copper Canyon, I am witnessing something that is typically missing in this day and age: a craftsman in the process of creating a custom product. In this case the craftsman, José “Che” Rentería, is creating a unique pair of huaraches, sandals, for me.

I arrive in Batopilas after an exhilarating drive down the winding dirt road from the mountain town of Creel and make my way over to the Plaza de la Constitución to find the sandal maker. His door is closed and the tools covering the two wooden workbenches in front of his house lie dormant. As with many things in Mexico, I must wait.

I arrive in Batopilas after an exhilarating drive down the winding dirt road from the mountain town of Creel and make my way over to the Plaza de la Constitución to find the sandal maker. His door is closed and the tools covering the two wooden workbenches in front of his house lie dormant. As with many things in Mexico, I must wait.

After dinner I return to find Che working under the harsh light of a bare incandescent bulb. He wears a white shirt with the words “Austin, TX” embroidered on the breast. The lines etched in his face reflect the rugged contours of the canyon in which he lives. I tell him that I want to buy a pair of his sandals. He measures my feet with a trained eye and says definitively, “Ocho.” He asks if I can come back tomorrow. I tell him I will return around noon, and he nods his assent. With that, I am off. No deposit, no order form…he doesn’t even know my name. It is comforting to know some people still operate on trust. Perhaps it is the result of living in a place where time moves very slowly.

Che was born in Batopilas in 1934 and has lived in the same house for all of his 72 years. He makes his living as a leatherworker and is a master of the craft. Fifteen years ago he started making the unique Tarahumaran huaraches, and he is the only person in Batopilas who makes them.

The huaraches worn by the Tarahumara Indians, a sturdy people native to the Copper Canyon area, are rather simple sandals. The soles are made of old tires; the pair made for me still includes some white letters indicating that they are “All Terrain” sandals. A leather footbed is glued to the rubber with what looks like Che’s own homemade glue. What makes the Tarahumaran huaraches so distinct from other sandals is a very clever lacing system. A single leather strap per sandal, originating between the big and index toes, is threaded through two holes cut into the sole to create support for the heel. The strap is then wrapped around the ankle three times before being tied to itself by the heel. The result is a very comfortable, stable sandal. In fact, the Tarahumara, considered to be the greatest long-distance runners in the world, chose their traditional huaraches over high-tech running shoes as they ran to first, second and fifth place finishes at the Leadville Trail 100, a high-altitude ultra-marathon in the Colorado Rockies. These are simple, sturdy and functional footwear.

I return the following day at noon and find Che playing with his grandchildren outside of his house. He retrieves the bottoms of my sandals and asks me to wait while he assembles the straps. Using an old blade, he removes the hard surface from the straps with an assured steadiness acquired from years of working in this medium. The trimming ensures that the leather against the feet will be soft and comfortable. As he works, he asks me where I am from. When I say Los Angeles, he asks, “Hollywood?” I tell him that I live very close to Hollywood, and he disappears into his house, returning with a stack of photos showing him at, of all places, Universal Studios Hollywood. A few years ago he went to California to visit his daughter who lives there, and I wonder if he felt as far from home as I do here in the bottom of a canyon in Mexico.

Che finishes his work and begins the tutorial. He ties my right sandal for me, going through the motions very slowly to ensure that I understand how it’s done. I find them to be much more comfortable than I had anticipated, and they fit perfectly. “¿Bueno?” he asks. “Muy bueno,” I respond. We shake hands, his skin almost as tough as the leather with which he works, and I stride off in my new huaraches. With every step, they will serve as reminders of this old-fashioned craftsman plying his trade in this beautiful village in the bottom of the Copper Canyon.

Kevin Maddaford

At California Native, we are always exploring new and exciting destinations to develop unique itineraries to offer our fellow travel enthusiasts.

At California Native, we are always exploring new and exciting destinations to develop unique itineraries to offer our fellow travel enthusiasts.

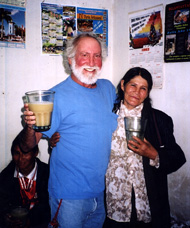

The strange-tasting drink, yellowish in color with a bubbly froth, is served warm for just a few coins, and is quite strong. It is not usually found in restaurants (a similar drink, chicha morada, made from blue corn, is sweet and sold everywhere like a soft-drink), but is sold by individuals, usually in the lower socioeconomic bracket, who have passed down the traditional recipes since pre-Inca times.

The strange-tasting drink, yellowish in color with a bubbly froth, is served warm for just a few coins, and is quite strong. It is not usually found in restaurants (a similar drink, chicha morada, made from blue corn, is sweet and sold everywhere like a soft-drink), but is sold by individuals, usually in the lower socioeconomic bracket, who have passed down the traditional recipes since pre-Inca times. We’ve spent an exciting day exploring the remote regions of

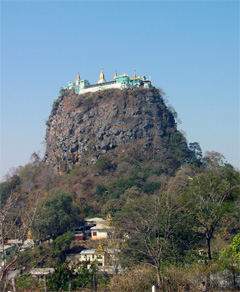

We’ve spent an exciting day exploring the remote regions of  There they stand in a line, offerings of food and flowers covering their pedestals. These figures are called Nats, spirits of the wind, earth, rain and sky, and in

There they stand in a line, offerings of food and flowers covering their pedestals. These figures are called Nats, spirits of the wind, earth, rain and sky, and in  Mt. Popa rises straight up from the plain, with a staircase winding to the temple at the top. Along the way are colorful Nat shrines, and pilgrims come from all over the country to give their offerings and make peace with the flamboyantly dressed representations of the spirits. Alongside the stairways, shops sell all variety of exotic merchandise, including bear paws, while frolicking monkeys run up and down the stairs begging for handouts.

Mt. Popa rises straight up from the plain, with a staircase winding to the temple at the top. Along the way are colorful Nat shrines, and pilgrims come from all over the country to give their offerings and make peace with the flamboyantly dressed representations of the spirits. Alongside the stairways, shops sell all variety of exotic merchandise, including bear paws, while frolicking monkeys run up and down the stairs begging for handouts. I arrive in Batopilas after an exhilarating drive down the winding dirt road from the mountain town of

I arrive in Batopilas after an exhilarating drive down the winding dirt road from the mountain town of  Before the arrival of the Spanish Conquistadors, Campeche was the principal town of the Mayas, who called it Ah Kin Pech (serpent tick), which the Spanish interpreted as “Campeche.”

Before the arrival of the Spanish Conquistadors, Campeche was the principal town of the Mayas, who called it Ah Kin Pech (serpent tick), which the Spanish interpreted as “Campeche.” Back at sea, the Spanish sailors worked their way down the coast until they arrived at Champotón. Locating food and water, the conquistadors also found themselves surrounded by Mayan warriors whose legions “seemed to multiply” until they outnumbered the Spanish 200 to one. The Mayans paid close attention to Captain Cordova, filling him with ten arrows that would eventually, five agonizing days later, claim his life. The Spaniards afterwards called the site costa de la mala pelea “the coast of the bad fight.”

Back at sea, the Spanish sailors worked their way down the coast until they arrived at Champotón. Locating food and water, the conquistadors also found themselves surrounded by Mayan warriors whose legions “seemed to multiply” until they outnumbered the Spanish 200 to one. The Mayans paid close attention to Captain Cordova, filling him with ten arrows that would eventually, five agonizing days later, claim his life. The Spaniards afterwards called the site costa de la mala pelea “the coast of the bad fight.” One commodity in particular led to this boom, the precious logwood tree, a medium-sized evergreen with yellow flowers. Profiteers quickly learned that the tree was also the source of rich violet and black dyes used by the natives to color their textiles. In Europe, these hues were produced by indigo dyes, exotic and affordable only to royalty and the rich. The introduction of the logwood dye provided a less-expensive alternative.

One commodity in particular led to this boom, the precious logwood tree, a medium-sized evergreen with yellow flowers. Profiteers quickly learned that the tree was also the source of rich violet and black dyes used by the natives to color their textiles. In Europe, these hues were produced by indigo dyes, exotic and affordable only to royalty and the rich. The introduction of the logwood dye provided a less-expensive alternative.