Most of us first heard about the bridge through the 1957 film, based on Pierre Boulle’s French novel. Set in a World War II Japanese POW camp in Burma, it is a fictional account of a battle of wills between a harrassed Japanese camp commander and a doggedly-stubborn British colonel. The story climaxes when allied commandos blow up the bridge.

The true story is different. During the Second World War, the Japanese planned a railway from Bangkok to Rangoon to shorten the distance between Japan and Burma by 1,300 miles. The railway would cross some of the wettest and most inhospitable terrain in Southeast Asia and require the construction of 688 bridges, but they considered it critical to the war effort.

For labor they used 250,000 Asian forced-laborers, mostly Thais, and more than 60,000 Allied prisoners—30,000 British, 18,000 Dutch, 13,000 Australians, and 700 Americans. Estimated to take five or six years to build, the project, which began on September 16, 1942, was completed after only 16 months, and cost the lives of 16,000 POWs and 75,000 Asian workers. The deaths from cholera, beri beri, malaria, typhoid, exhaustion and malnourishment, earned the railroad the name, “The Death Railway.”

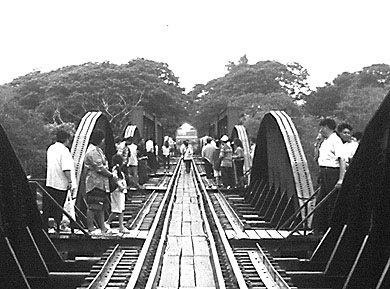

The Japanese actually constructed two parallel bridges across the River Kwai, just outside of the Thai town of Kanchanaburi—the first made entirely of wood, the second made of steel and concrete. The Allies destroyed both on February 13, 1945.

In the film the commandos detonated explosive charges fastened to the bridge’s supports. The real bridge was bombed. Failing to destroy the bridges with conventional bombs (some hitting POW camps) the American flyers brought in a new weapon, the AZON (Azimuth Only) bomb. The precursor of today’s “smart” bombs, it had a radio-controlled tail and ten times the accuracy of a conventional bomb.

After the war, engineers repaired the steel bridge over the River Kwai. It is still in use. Visitors to Kanchanaburi, Thailand, now walk across the bridge (the fortunate ones having the opportunity to witness me whistling the theme from the movie), and visit the Allied war cemetery and a museum run by Buddhist monks, featuring a reconstruction of a prisoner of war camp. The monks built the museum “not for the maintenance of hatred among human beings but to warn and teach us the lesson of how terrible war is.”